07 de Sep 2021 | Coffee

Effects of container shortages on international coffee trade

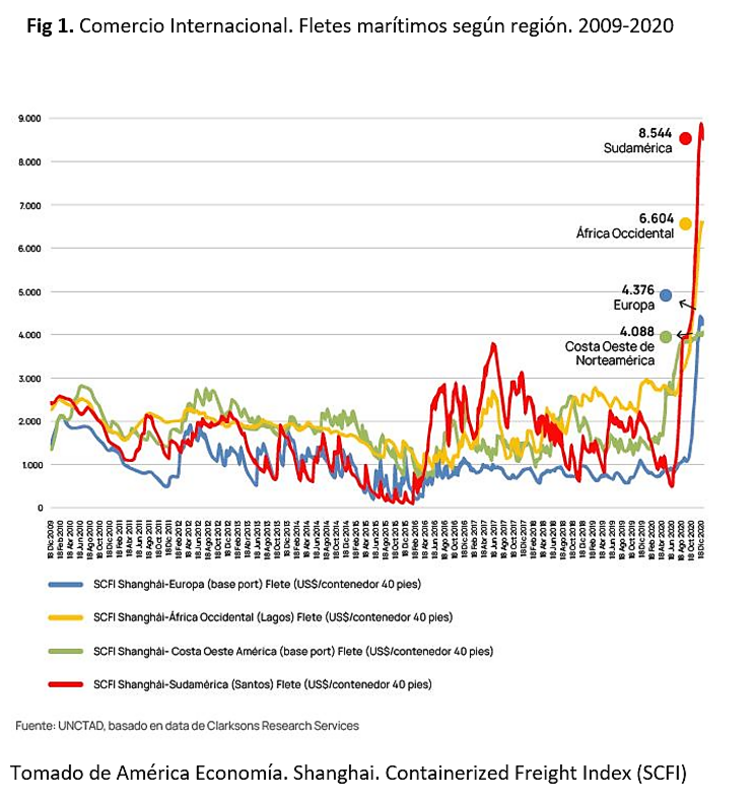

The Drewry World Container Index (2020) indicates that the cost increased on average 344% and it is the South American region that has been most affected.

Header image: Paita, main coffee exporting port in Peru - Photo of Terminales Portuarios Euroandinos (puertopaita.com)

The report of the drop in exports has surprised the Peruvian coffee sector, as its results contradict the production figures of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Irrigation, and is out of alignment with the commercial movement that most companies register. If the availability of coffee is not a problem, then what happens in international trade?

In the context of international trade, the shortage of containers is an increasingly important factor; it is associated with the 5% of world trade that has been paralyzed in China. Additionally, each new confinement implies adjustments that cause irregularities in its supply. The cancellation and alteration of itineraries left by the new normal of COVID has reduced the effectiveness and eficiency of the world programmed with algorithms that existed before the pandemic.

Increasing demand for containers in industries that use e-commerce is another external factor behind the shortage. This trend would continue until the end of the year and is explained, in part, by the transfer of household expenses in tourism and entertainment outside the home to individual purchases in online stores of medical laser pointer pen equipment and personal protection. This would also affect the products that containers usually use for their export operations.

This increased demand for containers in world trade and the chain slowed down by protocols have raised rates. For this reason, American roasters report significant increases in their operating costs, as well as delays in their shipments, which has resulted in the rise in the price of coffee (NBC, Wall Street Journal). Similarly, the effect is accentuated in South America (América Economía), where the size of the market does not favor the region: Felipe Astudillo from the Chilean Chamber of Commerce afirms: "If it weren't for Brazil, neither would ships come."

The main problem occurs in the South American region, according to UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), this region has the highest shipping cost, taking Santos (main export port and coffee exit port) and Shanghai for reference. This cost can be 25% higher than in Africa, 45% higher than in Europe, and double that of the East Coast of the United States.

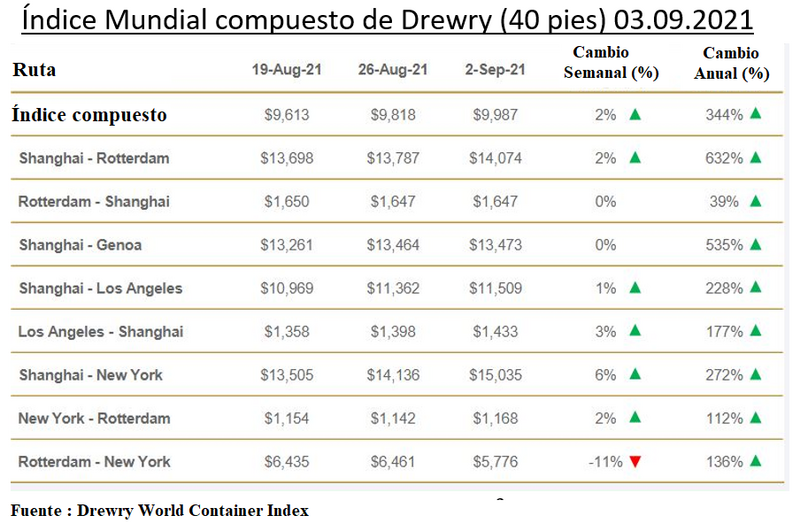

For the newspaper La República de Colombia, freight prices have quadrupled in the region, mainly affecting destinations in the United States and Asia. The cost of the container went from an average of US $ 2,000 at the end of 2019 to almost US $ 10,000 as of August of this year.

Bloomberg realizes that the main ports in China have a congestion of more than 50%, which generates volatility in price and availability. It should be noted that Shanghai is the main commercial port in the world, not only the main exporter, but also an importer. The outbreaks of COVID and the confinement that are generated here significantly affect the global logistics chain. Therefore, with the exception of Europe, the effect of the phenomenon is strongly felt in all regions: the Drewry World Container Index (2020) indicates that, on average, the cost increased by 344%.

Actions and reactions in the chain

For the European Coffee Federation, the reliability of shipping companies is less than 36%, the lowest in history. Additionally, trade continues to be delayed due to the lack of availability of containers. This has not affected the final prices of the coffee, but it has affected the payment to the producers, who do not charge until the container gets on the ship. In the best scenario, this situation would be regularized from March 2022. For this reason, patience together with the implementation of backup measures are necessary to operate under these conditions of uncertainty.

One month after the start of the coffee campaign, Colombia is planning to change the port of shipment, which increases costs and modifies times, but guarantees the operation. For ASOEXPORT (National Association of Coffee Exporters): "the repercussions of COVID had not been felt as much as at this time".

This week India has started a support program for its agricultural export operations that prioritizes coffee. It includes support in financing, adjustments in the management of ports and railways, protocols that allow the rapid mobilization of containers, and evaluation of the manufacture of containers.

In Brazil, CECAFE (Council of Exporters of Brazil) reports that its coffee industry is one of the hardest hit. Under normal conditions for its logistics, Marco Matos points out: "Brazil could be at an upper limit for exports, but now a part is in the port, shipments are canceled, there are dificulties and concerns about the future." Under current conditions: there is a lack of space on ships, shipments are postponed, ships are skipped, and space in port terminals is not enough.

In this context, for Guaxupe, long-term shipments are not a cause for concern, as customers are aware of logistics problems and the global situation. There has also been no renegotiation of the contracts already signed, they have remained active, discussed and resolved logistical problems identified within the months of the contract. The crisis is managed with information.

In Peru, the costs of these operations are usually relatively higher. For example, shipping a container from here to the United States costs 70% more than the reverse route due to the effects of distance and the flow of trade.

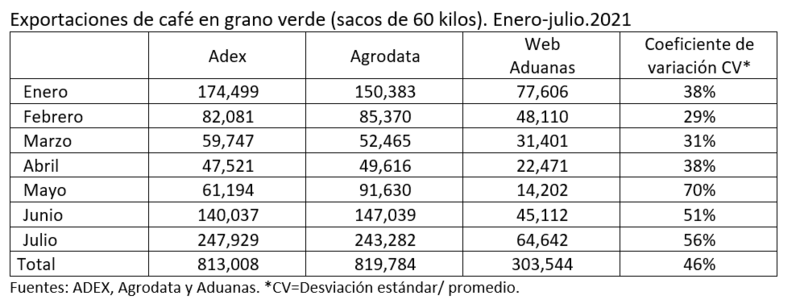

In this context, local actors involved in international trade need reliable and timely information. However, the total variability of the data on Peruvian coffee exports reported by the main sources consulted (Adex, Agrodata and Customs) is 46%, presenting substantial differences between their monthly export reports. For example, the public source of Customs reports on its web portal 303 thousand bags of coffee, far from the 813 thousand bags reported by the ADEX union and the 819 thousand reported by the private source Agrodata. This high variability between the export data of the aforementioned organizations reduces trust in them, since it ends up projecting a negative image for decision makers.

Due to the above, the Peruvian Chamber of Coffee and Cocoa considers it relevant to make an effort from the State to feed the export process with key and timely information, which promotes the quality control of the process, the guarantee of its accessibility and the support for export operations in today's reality.

The effort could contribute to the supporting arguments for the attributes of Peruvian coffee that are promoted in the foreign market and that constitute a message that generates confidence in the international buyer (B to B). This is evidenced by the strategic guidelines for the promotion of Peruvian coffee in the foreign market that the Chamber has drawn up within the framework of the Alliance for Sustainable and Competitive Coffee Project.

_________________________________________________________________

Sources:

1) Ben Thompson. (Marchs 22nd, 2021). Why is the cost of coffee rising? Expertssay a container shortage. WCNC

2) Esteban Feria (tuesday, August 31 of 2021). Crisis marítima en puertos de China y EE.UU. cuadruplicó los precios de los fletes. La República.

3) Cuprima. WHAT IS GOING ON THE COFFEE SUPPLY CHAIN?

4 SUBHAYAN CHAKRABORTY (SEPTEMBER 06, 2021). Emergency steps to stem container crisis expected by early next week. Money Control.

5) Virgínia Alves (August 27 of 2021). Gargalos logísticos no café: Tentando driblar problemas, setor precisa unir forças para atender mercado externo. Noticias Agrícolas

6) Header images: Noticias Agrícolas